Business.com aims to help business owners make informed decisions to support and grow their companies. We research and recommend products and services suitable for various business types, investing thousands of hours each year in this process.

As a business, we need to generate revenue to sustain our content. We have financial relationships with some companies we cover, earning commissions when readers purchase from our partners or share information about their needs. These relationships do not dictate our advice and recommendations. Our editorial team independently evaluates and recommends products and services based on their research and expertise. Learn more about our process and partners here.

Fast, Good or Cheap — The Iron Triangle

The iron triangle of product development has shortcomings. Learn why the lean startup process is the best way to achieve "fast, good and cheap," all in one project.

Table of Contents

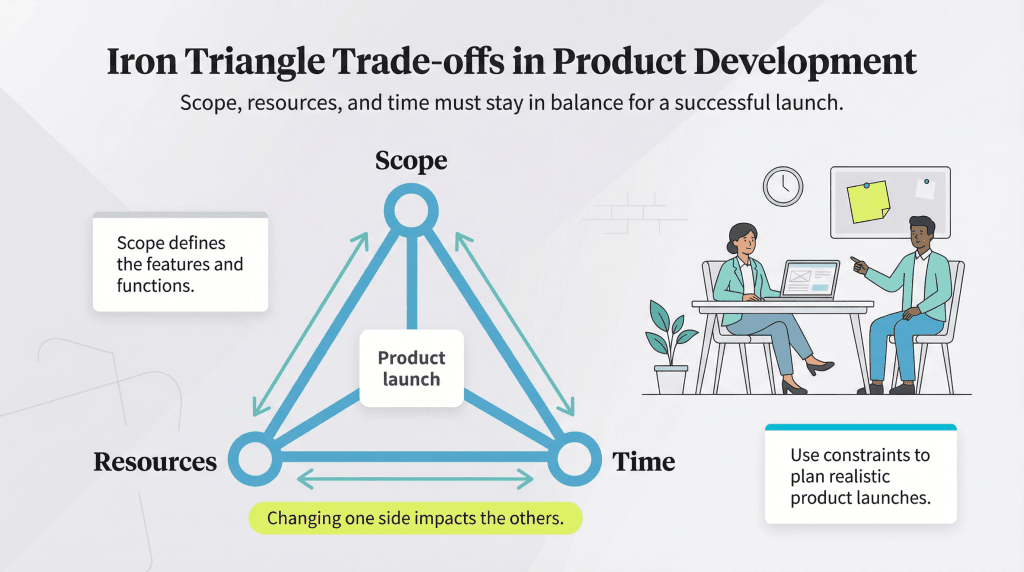

There’s an old saying in software development that goes something like, “Fast, good or cheap — pick two.” Known as the iron triangle, project management triangle or triple constraint, this concept is familiar to anyone who has ever felt the pressure of weighing the opposing forces of quality, speed and cost against one another.

The general concept is that you have three choices when making a product: Make it quickly, cheaply or well. While it has long been believed that it isn’t possible to accomplish all three, some now think it is. Focusing on values and eliminating assumptions are key to developing a valuable product.

What is the iron triangle?

The concept of the iron triangle has evolved from three general assumptions:

- You can develop something quickly and of high quality, but it will be very costly.

- You can develop something quickly and cheaply, but it will be of low quality.

- You can develop something of high quality and low cost, but it will take a long time.

In this video, we break down the iron triangle and the trade-offs between time, cost and scope.

Rafaël Van Coppenolle, product director at Nexapp, said that relying too heavily on the Iron Triangle can lead to compromised quality.

“If you cut too much from scope, time or budget, it could negatively affect the end product,” Van Coppenolle told us. “The key is balancing flexibility with the integrity of the product.”

Van Coppenolle also emphasized the importance of setting expectations with clear communication. He noted that without firm deadlines or budgets, “the project can easily spin out of control,” leading to overspending and under-delivery.

Let’s look at each aspect of the iron triangle and what they mean for product development.

Cheap and fast

If you develop something cheap and fast, you’ll sacrifice features or the quality of the product to get it done quickly. You create an acceptable prototype and can start receiving feedback on it immediately. This allows you to use feedback and improve your product, but the sacrifice may not be worth it. You could hurt your company’s credibility and create more problems for yourself down the road.

Salome Mikadze, co-founder at Movadex, explains why this approach can cost you customers in the long run.

“If there’s one truth I’ve learned, it’s this: your first version will always be wrong (sorry),” said Mikadze. “No amount of planning can predict exactly how users will behave. That’s why shipping fast is not optional — it’s survival. I’ve seen founders choose “fast and cheap,” thinking they’ll improve things later. The reality? Users remember their first experience. If it’s broken or clunky, they might never come back.”

Good and cheap

Another option is to create a high-quality product but spend as little money on it as possible. You’ll deliver a better product to your customers, but it could take a long time to finish it while staying under budget.

If you have the time to do a lot of research and product development in the beginning, this could have better results for your company. But in today’s market, businesses need to be flexible and able to act quickly, which isn’t likely with this method. Ultimately, because you never received feedback from your customers during development, you may create a high-quality product they don’t want. However, Van Coppenolle notes that there are exceptions to this rule — if you plan correctly.

“When choosing the ‘good and cheap’ route, businesses should be prepared for a longer timeline,” he said. “However, this doesn’t mean that customer satisfaction is at risk. By focusing on design and prototypes, businesses can gather feedback or even secure sales before fully developing the product. This allows for more certainty and reduces the risk of building something that doesn’t meet market needs. Breaking down the project into smaller, manageable pieces ensures that progress is still being made, even if the overall timeline is longer.”

Good and fast

Finally, you can create a high-quality product in as little time as possible. Out of the three options, most businesses prefer this one. You can create a good product in a short time, but it’s going to cost you. You’ll likely have to invest in a team to help you meet the demands of your timeline and the extra money you spend could be wasted if you have to redo the product.

Van Coppenolle said this path doesn’t always lead to the success businesses hope for. For example, it can be a costly strategy when companies assume that adding more people to a project will accelerate progress.

“While the intention is to speed things up, the reality is that more team members often lead to increased complexity and coordination challenges, which can slow down the process rather than enhance it,” Van Coppenolle explained. “Rarely does this approach yield the desired results — it often results in average outcomes and can introduce additional problems.”

According to Van Coppenolle, starting with a minimal, fast approach and refining it over time is typically more effective. “Trying to rush perfection can lead to higher costs and lower quality in the long run,” he said.

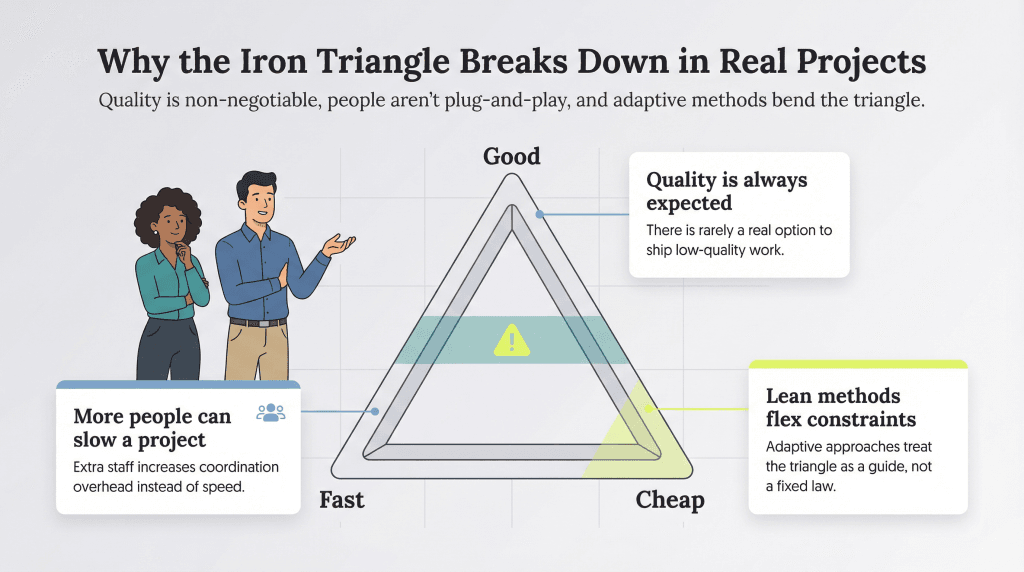

What are the problems with the iron triangle?

The iron triangle may seem like a straightforward framework, but it quickly runs into real-world complications. Here are some common issues that highlight why it’s not always a reliable guide for managing projects.

‘Quality’ is a universal expectation.

The first issue with the iron triangle is the definition of “good,” or the concept of quality. The triangle assumes that “fast and cheap” is an option, but in truth, delivering a low-quality product is seldom an actual option. Whether you’re releasing a product to market, completing a project for a client or delivering on an internal company project, quality is a universal expectation.

Adding more people can slow things down.

The second issue is known as The Mythical Man-Month or Brooks’ law, which states, “Adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.” While Brooks’ law refers specifically to software development, the concept applies to many types of projects.

This is often simplified by the metaphor “too many cooks in the kitchen,” as Van Coppenolle suggested above. The basic concept is that when you add more people to a problem, the additional communication overhead and complexity of team dynamics often have a negative effect on the timeline as a whole.

The lean method challenges the triangle.

The scenario above pretty much eliminates the combination of good and fast as a real option. That leaves us with good and cheap, but that means the project will take a long time. However, that doesn’t have to be the case if you use the lean method. Mikadze, who frequently utilizes the lean method, explains why the iron triangle can be a helpful framework if you don’t see it as unchangeable.

“The Iron Triangle … is a useful mental model,” she said. “It forces trade-offs and keeps expectations realistic, especially in early-stage product development. But in my experience, it’s not an absolute law – it’s a challenge to be solved.”

The triangle isn’t set in stone.

Van Coppenolle also told us that product development allows for much more flexibility than the iron triangle would suggest.

“While the iron triangle concept emphasizes the inflexibility of the ‘good, fast and cheap’ criteria, there are situations where these constraints have more flexibility,” he said. “For instance, when a project is in its early stages or when validating an idea, businesses can prioritize getting feedback quickly with less focus on perfection, allowing room to experiment with speed and lower costs.”

What is an example of the iron triangle?

The constraints (fast, good and cheap) are thought to be “iron” because you cannot change one constraint without affecting the others.

Let’s use the iron triangle to look at the constraints in project management for a software development team as an example. These are some of the constraints they’d face:

- The scope of the work, such as the functions and features necessary to deliver a working product

- The necessary resources, such as the team members and budget for delivering and executing the product

- The time it takes for the team to go to market and release the product

The goal of the iron triangle is to give a product team the necessary information to make trade-offs that ultimately help the business. For instance, if the team has a fixed scope, they may be halfway through the project and realize they are unable to meet the release date.

At that point, these are their options:

- Accept a later release date (time)

- Add more people to the project, ultimately raising the overall costs (resources)

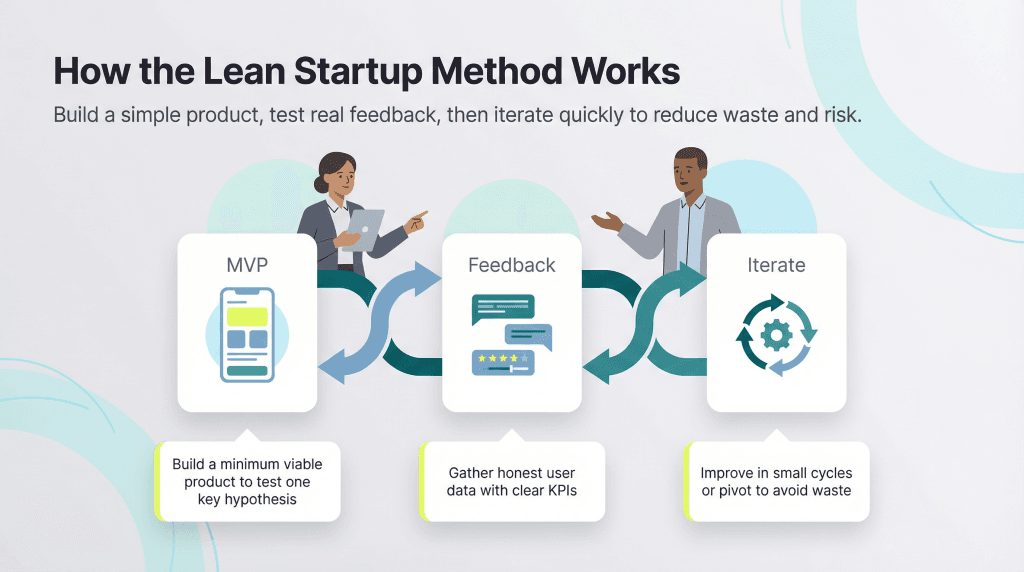

What is the lean startup method?

As mentioned above, the problems with the iron triangle leave us with one real option for product development: good and cheap. While this typically results in a slower development process, the lean startup method can help to speed things up.

The lean startup method, developed by Eric Ries in 2008, is a process for delivering products and businesses. Chronicled in Ries’ 2011 book The Lean Startup: How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses, this method is based on concepts borrowed from lean manufacturing as developed by Japanese automakers in the 1980s.

The lean startup method extols the concept that anything that does not deliver value to the end user is waste. This waste is combated by creating testable and measurable hypotheses and then measuring them against honest and meaningful key performance indicators (KPIs).

>>Read Next: 14 KPI Tools to Track Your Business’s Goals

Mikadze clarified that this approach can help you view your product development journey as valuable as the end goal.

“The lean startup method challenges the iron triangle by saying: You don’t have to pick two — you just have to iterate faster than everyone else. Instead of treating the first launch as the finish line, it’s the starting point for learning.”

Van Coppenolle explained the benefits of using this approach.

“The core advantage is that it eliminates uncertainty in software development by continuously testing and gathering feedback. Even when leaders, such as a CEO, request new features, you cannot be sure if they will bring more revenue or users without validating assumptions. Lean allows you to test your ideas quickly with minimal effort and based on the feedback, either build upon your hypothesis or pivot. By testing early, you avoid wasting time and money on features that might not deliver value.”

The lean startup method in practice

The first step is to build a minimum viable product (MVP), which is the simplest version of a product that can test your hypothesis and deliver the maximum amount of validated learning.

After creating your initial MVP, the next step is to iterate repeatedly, using tools like split testing and the predetermined KPIs. These tools will help you adjust that product with one of two outcomes: refine it to excellence or determine failure and pivot. Mikadze explained what this approach looks like for her team:

“At my firm, our process is simple:

- Launch an MVP with a clear disclaimer. Be upfront that things will improve.

- Get real user feedback immediately. Encourage early adopters to engage.

- Iterate in small, fast cycles. Instead of fixing everything at once, improve one thing at a time.

“This approach has helped us build and scale products without sacrificing speed, quality or budget,” she added. “It’s not magic — it’s just listening to users and adapting faster than the competition.”

How can you apply the lean process?

Armed with what we’ve learned about the shortcomings of the iron triangle, it is possible to deliver a fast, cheap and good project by applying the concepts of the lean process. With this process, you keep teams small because you know that too many cooks are going to make communication more difficult and limit your flexibility to deal with changing market demands.

Because you are just building an MVP at first, a significant upfront investment isn’t necessary. You are testing your hypothesis, so spending a lot of money or investing in other resources would be a waste if you’re wrong.

Keeping teams small and limiting the investment in the MVP lets you keep the project cheap. You’re also building the MVP to gain validated learning as soon as possible and deliver value to the end user.

By focusing on those values — and preventing a bloated scope full of assumptions and untested hypotheses — you can build fast. When limiting the work to the MVP, you get to market quickly with something of value.

Once you’ve released the initial MVP, you can continue to follow the lean principles, using validated learning and KPIs to decide what’s working and what’s not and iterate quickly. The reiterations and meaningful measurements will guide you toward the end goal of delivering a good product.

And there you have it: Fast, good and cheap, all in one project.

Skye Schooley and Natalie Hamingson contributed to this article.