Business.com aims to help business owners make informed decisions to support and grow their companies. We research and recommend products and services suitable for various business types, investing thousands of hours each year in this process.

As a business, we need to generate revenue to sustain our content. We have financial relationships with some companies we cover, earning commissions when readers purchase from our partners or share information about their needs. These relationships do not dictate our advice and recommendations. Our editorial team independently evaluates and recommends products and services based on their research and expertise. Learn more about our process and partners here.

Contingency Management Theory Explained

Learn how Fiedler's contingency theory helps leaders match their style to situations for better team performance.

Table of Contents

In the dynamic world of business management, one size rarely fits all when it comes to leadership and organizational strategy. Contingency theory in management recognizes this reality by proposing that the most effective leadership approach depends entirely on the specific situation at hand. Rather than prescribing universal management principles, this influential theory emphasizes the importance of matching leadership styles, organizational structures and decision-making processes to each business’s unique circumstances. Developed by pioneering researchers like Fred Fiedler in the 1960s, contingency theory revolutionized how we think about management effectiveness. It challenged traditional “one best way” approaches and introduced a more nuanced, flexible framework for organizational success.

Today’s fast-paced business environment makes contingency thinking more relevant than ever before. Modern managers face constantly shifting market conditions, diverse workforce expectations, technological disruptions and evolving customer demands that require adaptive leadership strategies. By understanding contingency theory and its various models, business leaders can make more informed decisions about when to be directive versus collaborative, when to centralize versus decentralize authority, and how to adjust their management style based on team maturity and project requirements. This comprehensive guide explores the core principles of contingency theory, examines key models like Fiedler’s LPC scale and situational leadership, and provides practical insights for implementing contingency thinking in real-world management scenarios.

What is contingency theory in management?

Contingency theory is a management theory that argues there is no single best approach to management; instead, it asserts that effective leadership is contingent on internal and external factors. The theory fundamentally recognizes that leadership effectiveness depends on matching the leader’s style to the specific demands of the situation they face.

The theory highlights the importance of self-awareness, objectivity and adaptability in determining the most effective leadership approach for a given situation. This adaptability is especially important given the diversity of the modern workplace, said Shwetank Dixit, founder of Voohy.com, a platform for leadership and career skills training.

“The workplace has changed and become more diverse today,” Dixit said. “Many companies have realized that managers cannot rely on just one way of managing and leading — and instead might need to adjust their leadership style based on the situation and people involved.”

Contingency theory origins and key contributors

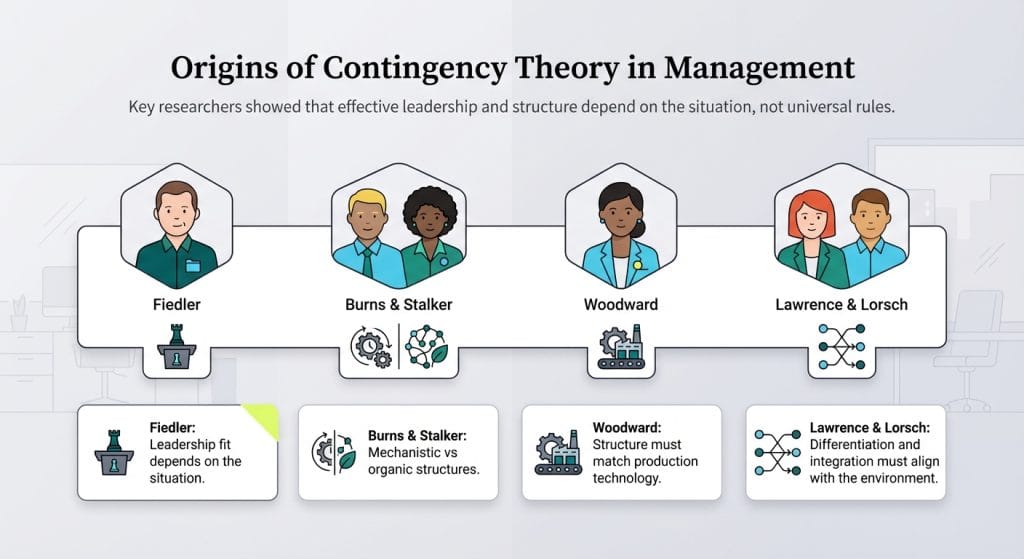

Contingency theory emerged in the 1960s through the work of several influential organizational researchers who challenged the notion of universal management principles. While Fiedler is best known for his leadership contingency model, other key contributors helped establish the foundational concepts.

- Fred Fiedler developed the most well-known contingency model of leadership, introducing the concept that leader effectiveness depends on matching leadership style to situational favorableness. His work in the 1960s shifted leadership studies from focusing solely on personality traits to examining how leadership styles perform in different contexts.

- Tom Burns and Graham Stalker contributed to contingency theory by identifying mechanistic versus organic organizational structures. Their research demonstrated that organizations in stable environments perform better with mechanistic (hierarchical, rigid) structures, while those in dynamic environments thrive with organic (flexible, decentralized) structures.

- Joan Woodward‘s research on technology and organizational structure showed how different production technologies require different organizational designs. She identified three types of production systems — unit, mass and process production — each requiring distinct organizational structures for optimal performance.

- Paul Lawrence and Jay Lorsch expanded contingency theory by examining how organizations manage differentiation and integration in complex environments. They proposed that organizations operating in complex environments must adopt higher degrees of both differentiation and integration to remain effective.

Fiedler’s contingency model explained

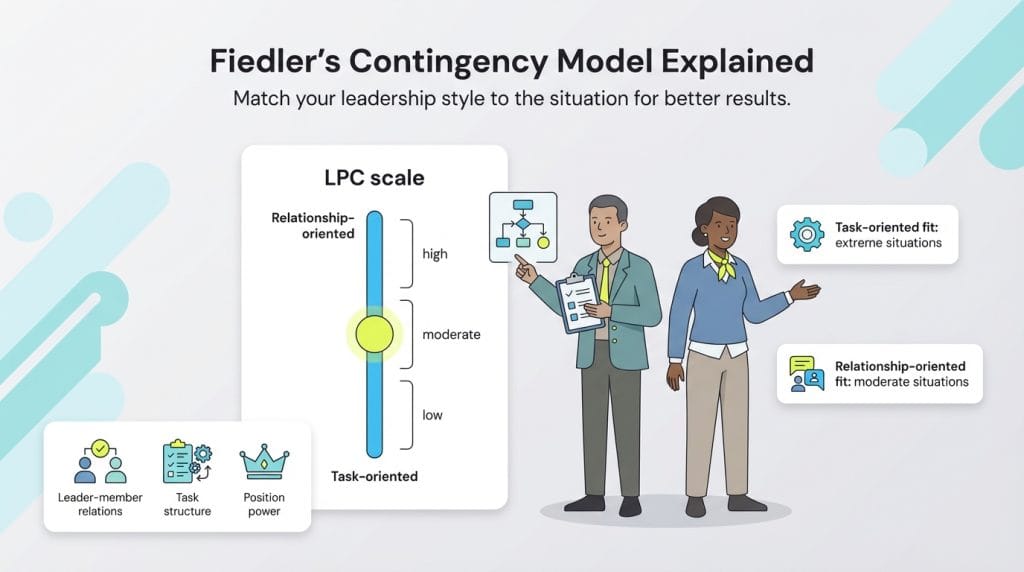

Fiedler’s contingency model proposes a simple concept: comparing your leadership style to the demands of a particular situation. The main aspects of the contingency approach are the LPC scale, situational favorableness and leadership style fit.

LPC scale

Fiedler created the least-preferred co-worker (LPC) scale to identify leadership styles. The scale measures whether managers take a task- or relationship-oriented approach. On an eight-point scale, it uses between 18 and 25 adjectives, such as pleasant and unpleasant, interesting and boring, or supportive and hostile, to describe co-workers.

A higher rating on the scale indicates a relationship-oriented leader skilled in building connections and managing interpersonal dynamics. Conversely, a lower rating suggests a task-oriented leader focused on efficiency and effectiveness. A score above 73 means they are a relationship-oriented leader, and anything below 54 means they are a task-oriented leader. Those who fall between 55 and 72 are considered both relationship-oriented and task-oriented leaders, which means they might need to delve further into other leadership theories to determine their preferred style.

Situational favorableness

Fiedler’s model calls for assessing a situation using situational contingency theory. The favorability of a situation depends on leader-member relations, task structure and position power.

- Leader-member relations refer to the degree of trust and respect team members have for their leader. Higher trust levels create more favorable conditions for leadership effectiveness.

- Task structure indicates how clearly defined and structured the work tasks are, with more structured tasks creating more favorable leadership conditions.

- Position power represents the formal authority a leader has over their team, including the ability to reward, punish or direct team members.

Strong trust between the leader and team members, clear task requirements and high position power contribute to a more favorable situation for effective leadership.

Leadership style fit

The leadership style fit component determines which approach works best by matching a leader’s natural style, identified through the LPC scale, with the situational favorableness of their environment. Fiedler’s research revealed that different leadership styles perform optimally under different situational conditions, creating a clear framework for when to apply task-oriented versus relationship-oriented approaches.

- Task-oriented leaders (low LPC scores) perform most effectively in two distinct scenarios: highly favorable situations where they have strong relationships, clear tasks and substantial authority, allowing them to focus on driving results efficiently; and highly unfavorable situations where poor relationships, unclear tasks and limited authority require decisive, directive leadership to provide structure and clarity during crisis or chaos.

- Relationship-oriented leaders (high LPC scores) excel in moderately favorable situations where mixed conditions, such as good relationships but unclear tasks or clear tasks but strained relationships, require diplomatic skills, consensus-building, and interpersonal finesse to navigate complexity and maintain team cohesion.

The key insight of leadership style fit is that neither leadership approach is universally superior; instead, effectiveness depends entirely on situational alignment. A relationship-oriented leader who excels at team building may struggle in a crisis requiring immediate decisions, while a task-oriented leader who thrives under pressure might damage morale in situations requiring collaboration and buy-in. This understanding helps organizations place leaders in situations that match their natural strengths while developing awareness of when their style may need adjustment or support from others with complementary approaches.

Variations of contingency theory

Several leadership theories have evolved from or complement Fiedler’s original contingency model, each offering different perspectives on leadership approaches.

Situational leadership

Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard’s situational leadership theory revolutionizes traditional leadership thinking by proposing that effective leaders must continuously adjust their approach based on their followers’ development level and task-specific readiness. This dynamic model recognizes that the same employee may require different leadership styles depending on their competence and commitment for particular tasks or responsibilities.

The theory identifies four distinct leadership approaches — directing (telling), coaching (selling), supporting (participating) and delegating — that correspond to followers’ evolving capabilities, from new team members who need clear instructions and close supervision to experienced professionals who thrive with autonomy and minimal oversight. This flexibility distinguishes situational leadership from Fiedler’s fixed-style approach, positioning leaders as adaptive coaches who modify their behavior to meet followers exactly where they are in their professional development journey.

Path-goal theory

Robert House’s path-goal theory states that successful leaders are strategic guides who adapt their approach to help team members reach their goals. The core concept revolves around leaders acting as pathway illuminators — they clarify expectations, provide necessary tools and training, remove bureaucratic roadblocks, and offer appropriate recognition to keep employees motivated and moving forward.

Unlike Fiedler’s model, which suggests leaders have fixed styles, path-goal theory assumes leaders can and should modify their approach depending on what their team members require to succeed in any given moment. This behavioral flexibility places the burden of adaptation squarely on the leader’s shoulders, requiring them to continuously assess whether their team needs directive guidance, supportive encouragement, participative collaboration or achievement-oriented challenges to maintain momentum toward organizational goals.

Decision-making theory

Decision-making theory, also called the Vroom-Yetton-Jago model, addresses a fundamental leadership challenge: determining when to make decisions independently versus involving team members in the process. This decision-making contingency theory provides leaders with a systematic framework for evaluating situational variables — including the importance of decision quality, the need for employee buy-in, available time constraints and team expertise levels — to determine the optimal level of participation.

Unlike other contingency theories that focus on broad leadership styles, this model specifically guides leaders through the decision-making process itself, helping them choose between autocratic approaches when speed and expertise are critical, consultative methods when input is valuable but final authority remains with the leader, or fully collaborative processes when team commitment and diverse perspectives are essential for successful implementation.

When and how to use contingency thinking in management

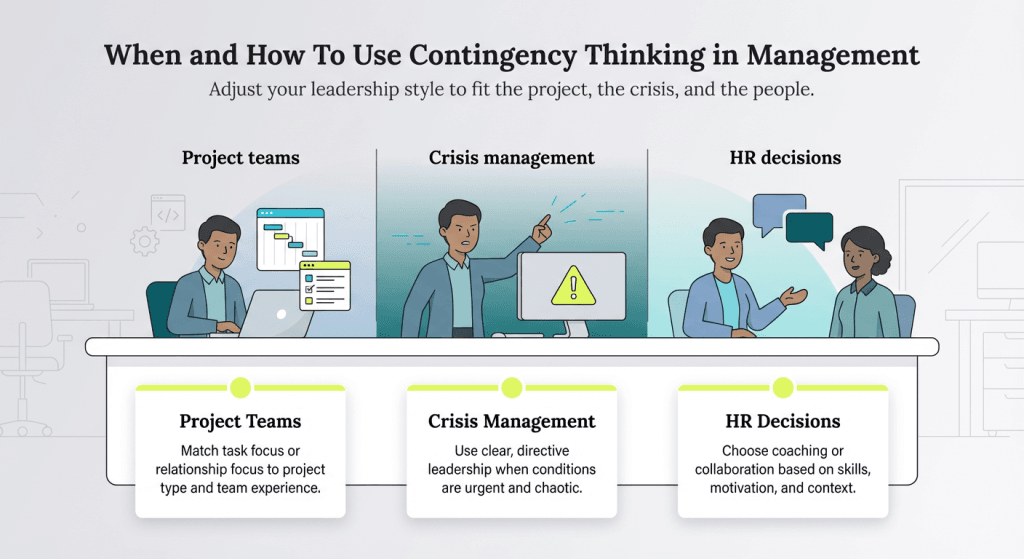

Contingency thinking proves particularly valuable in project teams, crisis management and HR decision-making, where situational factors significantly impact leadership effectiveness. See examples of contingency theory in management below.

Project teams

In project teams, contingency management helps leaders adapt their approach based on project complexity, team experience and timeline constraints. A task-oriented approach may work best for well-defined projects with tight deadlines, while relationship-oriented leadership might be more effective for creative projects requiring high collaboration.

Example: A software development manager leads two different projects simultaneously. For Project A — a routine system update with a three-week deadline and experienced developers — they adopt a task-oriented approach, providing clear specifications, daily check-ins and focused deliverables. However, for Project B — an innovative AI feature requiring creative problem-solving with junior developers — they shift to relationship-oriented leadership, facilitating brainstorming sessions, encouraging experimentation, and building team confidence through mentoring and collaborative decision-making.

Crisis management

During crisis management, leaders must quickly assess situational favorableness and adjust their leadership style accordingly. Crisis situations often create highly unfavorable conditions with poor communication, unclear tasks and limited formal authority, making task-oriented leadership more effective for rapid decision-making and clear direction.

Example: When a major data breach hits the company at 2 a.m., the IT director immediately switches from their usual collaborative leadership style to a highly directive, task-oriented approach. They bypass normal committee processes, assign specific roles to each team member, establish a command center for centralized communication, and make rapid decisions about system shutdowns and customer notifications. Once the immediate crisis is contained, they return to a more participative style to conduct the post-incident review and develop long-term security improvements.

HR

In HR decision-making, contingency thinking helps managers tailor their approach to different employee situations, performance issues and organizational changes. The principle applies when determining whether to use directive coaching for skill gaps versus collaborative problem-solving for motivation issues.

Example: An HR manager encounters two performance issues in the same week. For Employee A, a new hire struggling with specific technical skills, they implement a directive coaching approach with structured training plans, clear performance metrics and regular skill assessments. For Employee B, a veteran team member whose performance has declined due to apparent disengagement, they adopt a collaborative approach — conducting one-on-one discussions to understand underlying concerns, jointly developing career development plans and exploring flexible work arrangements that address the employee’s changing life circumstances.

Strengths and criticisms of contingency approach

A contingency approach has several strengths while also facing legitimate criticisms from management researchers. See the advantages and disadvantages of contingency theory below.

Strengths

- Flexibility represents the primary strength of contingency theory, as this management model recognizes that different situations require different leadership approaches rather than applying one-size-fits-all solutions. The theory acknowledges the complexity of real-world leadership challenges and provides a framework for making situational assessments.

- Realism distinguishes contingency theory from earlier management theories that sought universal principles. The approach recognizes that organizational environments are dynamic and that effective leaders must adapt to changing circumstances rather than rigidly applying predetermined strategies.

Criticisms

- Complexity is the main criticism of contingency theory, as it can be difficult to accurately assess all situational variables and determine the optimal leadership approach. The theory requires leaders to simultaneously evaluate multiple factors and make nuanced judgments about situational favorableness, often under time constraints.

- The lack of universal guidance with this model can leave leaders uncertain about how to proceed, particularly when situational factors are ambiguous or conflicting. Critics argue that the theory’s emphasis on situational fit may discourage leaders from developing more flexible leadership skills or adapting their natural style when necessary.

Comparison table: Contingency models at a glance

See how contingency theory and its variations compare in the chart below.

Model | Focus | Key Element |

|---|---|---|

Fiedler’s contingency model | Matching fixed leadership style to situation | LPC scale and situational favorableness |

Situational leadership | Adapting leadership style to follower readiness | Four leadership styles based on follower competence and commitment |

Path-goal theory | Leader behavior to motivate followers | Clarifying paths to goals and removing obstacles |

Decision-making theory | Participative decision-making levels | Involving team members based on situational characteristics |

How to implement contingency management theory

While every business owner has their own way of leading their company, the contingency approach calls for focusing on a specific issue and determining how a leader may need to adjust their leadership style depending on the pressing concern. For modern applications of contingency management theory, here are a few ways to implement the contingency model at your organization.

Classify your organization with three variables in Fiedler’s contingency theory.

You can classify your business using these three variables:

- The degree to which your employees accept you as their leader

- The level of detail used to describe employees’ jobs

- The level of authority you possess in your position at the company

To effectively assess these variables, conduct regular one-on-one meetings with team members to gauge their trust and acceptance of your leadership, while also evaluating whether they seek your guidance voluntarily or seem resistant to direction. Examine your current job descriptions and standard operating procedures to determine if roles are clearly defined with specific outcomes, or if employees operate with significant ambiguity in their daily tasks. Finally, honestly evaluate your formal authority by considering whether you can make independent decisions about hiring, budgets and policy changes, or if you frequently need approval or input from others.

Once you understand your position across these three dimensions, you can determine your situational favorableness and adjust your leadership style accordingly — favoring task-oriented approaches in highly favorable or unfavorable situations, and relationship-oriented leadership in moderately favorable conditions.

Understand how internal and external factors affect your business.

Fiedler’s contingency theory says there are various internal and external factors that influence an organization’s optimal structure. Internal factors include the business’s size, the technology used, the leadership style and how the business adapts to strategic changes. Most of the time, business owners can’t control outside factors — such as the marketplace and customer orientation — which means they should address these issues differently than they would internal factors. It’s crucial for leaders to consider these external and internal factors before they determine their leadership style. The most effective approach is to adapt their leadership style to the situation.

Conduct regular environmental scans that assess both controllable and uncontrollable variables affecting your organization. For internal factors you can influence, like team structure, communication systems or skill development programs, develop proactive strategies that align with your preferred leadership approach and organizational goals. However, for external factors beyond your control, such as economic downturns, regulatory changes or competitive pressures, focus on building organizational agility and developing contingency plans that allow you to pivot your leadership style quickly.

Create a simple matrix that categorizes current business challenges as either internal/controllable or external/uncontrollable. Then, develop different response strategies for each category, ensuring your leadership approach remains flexible enough to address both types of situational demands effectively.

Evaluate your leaders using Fiedler’s LPC scale.

The LPC scale is Fiedler’s primary tool for determining whether a leader is naturally task-oriented or relationship-oriented in their management approach. To implement this assessment, have leaders think of the co-worker they have had the most difficulty working with throughout their career. Then, ask them to rate that person on 16 to 18 bipolar scales using descriptive pairs like friendly/unfriendly, cooperative/uncooperative or supportive/hostile.

Leaders who score high on the LPC scale (giving relatively positive ratings even to their least preferred co-worker) tend to be relationship-oriented, focusing on maintaining good interpersonal connections and team harmony. Conversely, leaders with low LPC scores (rating their least preferred co-worker very negatively) are typically task-oriented, prioritizing job completion and performance over relationship maintenance.

Once you’ve administered the LPC assessment to your leadership team, use the results to make strategic placement and development decisions rather than trying to change their fundamental leadership style. Task-oriented leaders (low LPC scores) perform best in either highly favorable situations where they have strong relationships, clear tasks and sufficient authority, or in highly unfavorable situations where decisive action and clear direction are essential for organizational survival. Relationship-oriented leaders (high LPC scores) excel in moderately favorable situations where building consensus, managing conflict and motivating employees become crucial for success.

Consider rotating leaders between different projects or departments based on their LPC scores and the situational demands, and provide targeted coaching that helps them recognize when their natural style may need adjustment rather than attempting to fundamentally alter their leadership personality.

Alternatives to Fiedler’s contingency management theory

While contingency theory allows for great flexibility within the workplace, combining it with insights from other popular theories can elevate your management effectiveness even further.

“What I appreciate most about leadership theory is that, for the most part, there is no right or wrong or one size fits all,” said Laurie Cure, an executive coach and CEO of Innovative Connections. “Every organization or business and every leader really needs to assess what approach is best for them — and often, it is situational.”

Here are some alternative management theories to consider.

Covey management theory

Covey management theory, outlined in Stephen Covey’s book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People (Simon and Schuster, 1989), emphasizes personal and organizational growth through seven key habits: being proactive, setting clear goals, prioritizing tasks, fostering collaboration, listening and understanding, cooperating and allowing for self-care. Covey’s approach encourages leaders to create a positive and communicative work environment.

Drucker management theory

Drucker management theory highlights results-oriented leadership, decentralization and continuous learning. Drucker advocated for setting clear goals, empowering employees and fostering innovation through decentralized decision-making. Drucker, known as the “father of modern management,” also highlighted the importance of organizational culture and corporate social responsibility in driving long-term success.

Follett management theory

Follett management theory emphasizes collaboration and employee engagement. Mary Parker Follet advocated for “power with” rather than “power over” to create reciprocal relationships between leaders and workers. Follett’s principles of integration, conflict resolution and shared group power encourage teamwork, open communication and mutual respect, thereby increasing morale and productivity.

Fayol management theory

Fayol management theory outlines five core functions: planning, organizing, commanding, coordinating and controlling. The theory’s creator, Henri Fayol, also introduced 14 principles, such as division of work, authority and unity of command, to enhance organizational effectiveness. Although this model is rooted in industrial practices, its ideas still provide valuable guidance for modern small businesses that are seeking efficient leadership and teamwork.

Juran management theory

Juran management theory focuses on three key principles: quality planning, quality control and quality improvement. Joseph Juran’s approach stresses continuous quality enhancement by understanding customer needs and engaging all levels of the organization. Juran’s commitment to quality management has influenced modern practices, including Six Sigma and lean manufacturing.

Kanter management theory

Kanter management theory centers on fostering positive change through six principles: showing up, speaking up, looking up, teaming up, never giving up and lifting others up. Rosabeth Moss Kanter’s approach promotes employee empowerment, collaboration and resilience. The theory encourages managers to create a supportive environment that boosts morale, productivity and openness to change.

Mayo management theory

Mayo management theory, based on Elton Mayo’s historic Hawthorne experiments, asserts that employees are motivated more by social and relational factors than by monetary rewards. Mayo’s approach emphasizes the importance of group cohesion, communication and positive interpersonal relationships to improve workplace productivity and morale.

FAQs about contingency theory

Source interviews were conducted for a previous version of this article.